Tundra Swan

General Description

Known by many in North America as the Whistling Swan, the Tundra Swan is a large, white bird, with a long neck held straight up. It has a black bill with yellow patches in front of its eyes, although the yellow is not always present. The juvenile is gray with a pink bill and black legs, but it becomes whiter through the winter because of continuous molting. Males and females look alike.

Habitat

Tundra Swans nest in the wet Arctic tundra and are generally found near the coast. During migration and through the winter, they inhabit shallow lakes, slow-moving rivers, flooded fields, and coastal estuaries. When Trumpeter Swans first reappeared in Washington, there was a habitat separation between the two swans, with the Trumpeters on fresh water and Tundras on salt water. This separation is no longer seen, and mixed flocks are common.

Behavior

During the breeding season, Tundra Swans forage mostly on the water, using their long necks to reach as much as three feet below the water's surface. During migration and in winter, much of their feeding is on land in fields. A long-lived species, they form long-term pair bonds.

Diet

Historically Tundra Swans ate invertebrates and submerged, aquatic vegetation, but severe declines in this food at migratory stopover and wintering areas have led the swans to shift to a winter diet of mostly grains and cultivated tubers left in agricultural fields through the winter. In summer, their diet consists of new shoots, tubers, and seeds.

Nesting

Nests are located near a lake or other open water, in an area with good visibility. Both parents help build the nest, which is a large, low mound of plant material with a depression in the center. The pair may reuse the nest from year to year. The female incubates the 4 to 5 eggs for about a month, with the male assisting. After the eggs hatch, both parents tend the young, leading them to sources of food where the young feed themselves. They first fly at 2 to 3 months, but stay with the parents at least through the first winter.

Migration Status

Tundra Swans migrate long distances in family groups. They leave the nesting area in late summer and stage in nearby estuaries before heading to the wintering grounds in mid-fall. In the spring, the birds make shorter flights with more stopovers than in the fall.

Conservation Status

The most numerous and widespread of the North American swans, the Tundra Swan is less affected by human settlement than the larger Trumpeter Swan. Destruction of wetlands in the winter range has reduced former food sources, but the Tundra Swan has adapted by shifting its winter habitat to agricultural fields. Lead poisoning has long been a problem for this species, because ingesting only a few lead pellets can kill a swan. This usually affects only a few birds, but large die-offs have occurred. The population appears stable. Limited hunting occurs in some western states, but not Washington.

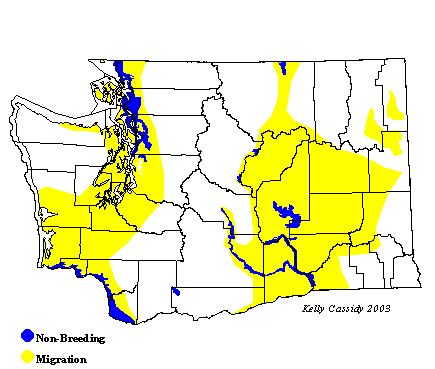

When and Where to Find in Washington

Tundra Swans are common in fresh- and saltwater habitats throughout the lowlands of northwestern Washington from November to April. Almost 2,000 winter in Skagit County. In eastern Washington, wintering swans are present, but less common, from mid-November to mid-March, and are more common during migration (mid-March to mid-April, and mid-October to mid-November). Small flocks come through the Turnbull National Wildlife Refuge (Spokane County), and about a thousand winter at the Ridgefield National Wildlife Refuge (Clark County) along the Columbia River.

Abundance

Abundance

| Ecoregion | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Oceanic | ||||||||||||

| Pacific Northwest Coast | U | U | U | R | R | R | U | U | ||||

| Puget Trough | C | C | C | U | U | C | C | |||||

| North Cascades | ||||||||||||

| West Cascades | C | C | C | U | F | C | C | |||||

| East Cascades | R | R | R | R | R | |||||||

| Okanogan | U | F | U | F | U | |||||||

| Canadian Rockies | F | F | F | F | U | F | F | |||||

| Blue Mountains | R | R | R | R | ||||||||

| Columbia Plateau | U | F | F | R | F | F | U |

Washington Range Map

North American Range Map

Family Members

Fulvous Whistling-DuckDendrocygna bicolor

Fulvous Whistling-DuckDendrocygna bicolor Taiga Bean-GooseAnser fabalis

Taiga Bean-GooseAnser fabalis Greater White-fronted GooseAnser albifrons

Greater White-fronted GooseAnser albifrons Emperor GooseChen canagica

Emperor GooseChen canagica Snow GooseChen caerulescens

Snow GooseChen caerulescens Ross's GooseChen rossii

Ross's GooseChen rossii BrantBranta bernicla

BrantBranta bernicla Cackling GooseBranta hutchinsii

Cackling GooseBranta hutchinsii Canada GooseBranta canadensis

Canada GooseBranta canadensis Mute SwanCygnus olor

Mute SwanCygnus olor Trumpeter SwanCygnus buccinator

Trumpeter SwanCygnus buccinator Tundra SwanCygnus columbianus

Tundra SwanCygnus columbianus Wood DuckAix sponsa

Wood DuckAix sponsa GadwallAnas strepera

GadwallAnas strepera Falcated DuckAnas falcata

Falcated DuckAnas falcata Eurasian WigeonAnas penelope

Eurasian WigeonAnas penelope American WigeonAnas americana

American WigeonAnas americana American Black DuckAnas rubripes

American Black DuckAnas rubripes MallardAnas platyrhynchos

MallardAnas platyrhynchos Blue-winged TealAnas discors

Blue-winged TealAnas discors Cinnamon TealAnas cyanoptera

Cinnamon TealAnas cyanoptera Northern ShovelerAnas clypeata

Northern ShovelerAnas clypeata Northern PintailAnas acuta

Northern PintailAnas acuta GarganeyAnas querquedula

GarganeyAnas querquedula Baikal TealAnas formosa

Baikal TealAnas formosa Green-winged TealAnas crecca

Green-winged TealAnas crecca CanvasbackAythya valisineria

CanvasbackAythya valisineria RedheadAythya americana

RedheadAythya americana Ring-necked DuckAythya collaris

Ring-necked DuckAythya collaris Tufted DuckAythya fuligula

Tufted DuckAythya fuligula Greater ScaupAythya marila

Greater ScaupAythya marila Lesser ScaupAythya affinis

Lesser ScaupAythya affinis Steller's EiderPolysticta stelleri

Steller's EiderPolysticta stelleri King EiderSomateria spectabilis

King EiderSomateria spectabilis Common EiderSomateria mollissima

Common EiderSomateria mollissima Harlequin DuckHistrionicus histrionicus

Harlequin DuckHistrionicus histrionicus Surf ScoterMelanitta perspicillata

Surf ScoterMelanitta perspicillata White-winged ScoterMelanitta fusca

White-winged ScoterMelanitta fusca Black ScoterMelanitta nigra

Black ScoterMelanitta nigra Long-tailed DuckClangula hyemalis

Long-tailed DuckClangula hyemalis BuffleheadBucephala albeola

BuffleheadBucephala albeola Common GoldeneyeBucephala clangula

Common GoldeneyeBucephala clangula Barrow's GoldeneyeBucephala islandica

Barrow's GoldeneyeBucephala islandica SmewMergellus albellus

SmewMergellus albellus Hooded MerganserLophodytes cucullatus

Hooded MerganserLophodytes cucullatus Common MerganserMergus merganser

Common MerganserMergus merganser Red-breasted MerganserMergus serrator

Red-breasted MerganserMergus serrator Ruddy DuckOxyura jamaicensis

Ruddy DuckOxyura jamaicensis